The goal of every organization is to provide a safe and inclusive environment to everyone who is involved in their programs. From the athletes, coaches , officials, and the spectators, the NLBA wants everyone to feel safe and supported in their endeavors. While every situation is different and every individual is different in how they perceive situations, it is important for the NLBA to provide resources and information to everyone to help give individuals the ability to foster athlete’s mental and physical wellbeing as well as provide those save environments to do that in. The Coaching Association of Canada (2020) reflects this perspective in its definition of Safe Sport: “Our collective responsibility is to create, foster and preserve sport environments that ensure positive, healthy and fulfilling experiences for all individuals. A safe sport environment is one in which all sport stakeholders recognize, and report acts of maltreatment and prioritize the welfare, safety and rights of every person at all times.” When the priority is optimizing the sport environment, the prevention of maltreatment or harms becomes a natural by-product. There are various forms of maltreatment in sport including but not limited to psychological, physical, sexual, neglect, grooming and failure to report maltreatment. Your child could be experiencing one or multiple forms of maltreatment. As parents and coaches, it is important to be able to recognize the signs that maltreatment may be happening. Some of these signs include but aren’t limited to a change in personality, your child not wanting to go to their sessions, any anxiety or anxiousness about participating that they didn’t have before. While these types of signs may be associated with other areas of an individual’s life, not necessarily maltreatment, it is a sign for you to start inquiring and digging deeper into what is happening in their lives. Maltreatment doesn’t only happen by a coach or person in authority. It can happen in a peer-to-peer setting such as through bullying or harmful behaviors towards each other. Maltreatment also doesn’t only happen in the training facility; it can happen at events outside of the training sessions such as informal get togethers, or even through online social media. Ensure activities are done in groups with other people around. Canada Basketball and the NLBA have the rule of 2 in place with the goal of ensuring interactions and communications are open, observable, and justifiable. While it is geared towards coach athlete interactions it is recommended to be used in all situations where adult/child interactions are occurring. Some red flags to watch for within a program would be things like: inappropriate private conversations through text messages or DM’s with the individual, verbal abuse from a person in authority such as a coach towards an athlete, the feeling of unrealistically high expectations followed by excessive punishment if not achieved. Other things to be aware of include when coaches are isolating the individual from the rest of the group, a coach failing to ensure safety of the individuals by using unsafe equipment or forcing participation when injured or unwell. While these signs are not exclusive and may be observed in other situations than maltreatment if you have a bad feeling about a situation or program it is worth looking into further. Over the years education pieces have changed, there are many resources out there available to people to take that promote safe sporting environments as well as help educate individuals on how to recognize, prevent and address maltreatment in sport. Most recently the Coaches Association of Canada has come up with a free NCCP course called Safe Sport which can be taken by anyone and helps give individuals the tools needed to create a culture where everyone can thrive safely. The NLBA has recently mandated that all its board members, staff, and coaches complete this Safe Sport course. And NABO has mandated that its officials have this course completed as well. We will also be requiring all provincial team athletes and parents complete this course in the future. It is a great resource to provide knowledge and tools in the hands of everyone to create safe sporting environments. In addition to this training the NLBA also requires that all of its coaches complete a vulnerable sector search with the RNC/RCMP and provide a clear record every year. Our coaches are also required to be NCCP certified which includes respect and ethics training as well. There have been many stories coming to light of maltreatment of athletes in various sports, often these don’t come into light until many years after the events have occurred. It is important that we provide safe spaces to allow for individuals to feel protected, should they come forward. One additional resource the NLBA is introducing as of January 15, 2022, is an anonymous reporting portal on our website. Here you will be able to report incidents of suspected maltreatment to a committee which will investigate these reports. All reports will be kept on file to reference and be monitored for any patterns that may emerge. There will be an independent committee that will investigate and take action where needed from these reports in alignment with our Athlete Protection Guidelines. It is everyone’s job to contribute to a safe sport environment. Parents, athletes, officials, coaches, board members all play a role in the recognition and prevention of maltreatment in the NLBA environment. Thank you for doing your part. Links: NLBA Safe Sport Information: https://www.newfoundlandlabradorbasketball.com/safe-sport NLBA Safe Sport Reporting Form: Safe Sport Training: https://safesport.coach.ca/participants-training NLBA Athlete Protection Guidelines: https://irp.cdn-website.com/08525354/files/uploaded/2021%20Athlete%20Protection%20Guidelines.pdf

The final element of quality coaching is attention to detail. Like fitness, the evidence of attention to detail is a little trickier to define and may be more readily understood by those involved, but can be discerned over time in a team’s execution. In this instance, it is often easier to discern a lack of attention to detail as opposed to its more positive counterpart. We can often sense a lack of attention to detail when we see players used out of position, or in ways that are counter to their natural skills or inclinations. We see it when players are used repetitively in situations or circumstances that they are not comfortable or productive in, or when a team makes no attempt to understand the underlying ideas that the opposition is employing to fuel their success. We all have a pretty good idea about what a poorly organized team looks like. The important distinction then is to get a firm grasp on when we are watching a team that pays attention to detail. The first point is not to confuse attention to detail with execution. Often we feel that if a team executes its system, with proper spacing or the right defensive principles, then attention is being paid to detail. After all, the players are doing the right things. Attention must be paid if the players are all moving in the same direction. As we have discussed earlier, proper execution often has less to do with quality coaching and more to do with the experience level of the players involved. The coach may pay no attention to detail but have a group of veteran players that understand the importance of knowing their lines. These players have enough collective service to know that if everyone is doing whatever they want, there is little chance of a positive outcome. However, if everyone follows the script and does their job, much can be salvaged. The cursory contemplation of whether a team executes well does not necessarily reveal attention to detail. Attention to detail is more revealed in the way a team prepares to play. This is often what is referred to as situational coaching. I not only prepare my team in the standard means of what we do and how we do it, but I also make sure they understand as many of the various situations we can find ourselves in and what we want to do in these circumstances. In basketball, if we are up 1 point with 30 seconds left and are on defence how aware are we of what the other team will attempt and how ready are we to break-up the play. In football, how well do we know the other team’s goal line plays and what they will run in crucial situations. This knowledge is often the direct result of a coach’s willingness to engage in meticulous tape study and create a knowledge base of what are the opponent’s tendencies and crutches. Taking away these tendencies, or least the attempt to take them away, is the attention to detail that often separates the quality of coaching we are watching. In various sports, the manipulation of time outs or clock management can also be important signs of attention to detail. Knowing your players to the point that you are aware of when they can play through difficult situations versus when you need to interject yourself into the process to change the course of events. Often lesser coaches will use timeouts or make play calls like it is from a manual. In this situation, you are less likely to be second guessed after a negative outcome if you follow this set of choices. In situations where jobs are on the line, this may even be understandable. The real quality coach has a feel for execution and when their input has real value and will make decisions to reinforce the confidence they have in their players when in a situation where things do not look good for them. They know that if they allow things to continue unchecked, the opposition will eventually make a choice that favours them if they are left without the ability to consult their own coach. All of these situations are better indications of attention to detail then plain execution. In the same vein as the above, is the ability of a coach to understand how to tilt those few crucial possessions in their favour to help their team be successful in a close game. They may create a match-up that seems to favour the other team, but when the team bends their offense to try and take advantage of the match-up, it disrupts their flow and allows the coach's team to enjoy a crucial period of success. Similarly, they will know which players they can allow to have certain opportunities because it detracts from the concepts or players that help that team be successful and win games. These subtle disruptions of a game's flow are often the small advantages that add up to a team being able to have success. Another thing that you see in teams that pay attention to detail is the ability to be calm or composed in key situations. When attention is paid to detail and the situations that arise in games, then players grow comfortable with these situations and what must be done. They may or may not be able to execute, but they do not fail because they are flustered or rushed. Their awareness of what needs to be done gives them a sense of calm. You will also see growth in young players, while they may be flustered in one situation, the next time they encounter that situation adjustments will have been made and they will know their role and understand what they are trying to accomplish. These teams just seem to understand what needs to be done and who needs to be in charge and what they are looking for. Finally, a coach who pays attention to detail understands what their teams need from them. In many cases, any coach can detect that something is not going properly or execution is off. The key is in knowing what each player needs to hear to help them get to the right place. A coach who pays attention to detail will have studied enough solutions and spent enough time on various skills and tactics that they will know what the problem is, how it can be fixed and what a player needs to hear to make those adjustments. Coaching is often the ability to get someone to do what is in their own best self interest even if they do not understand that. In this regard, you have to know how to phrase things to help players get to where they need to be in order to enjoy success. This comes from paying attention to the details of who you are talking to and how they need to be redirected. We know we are looking at a well coached team when we see evidence of physical fitness, player improvement and attention to detail. Is the team we are watching able to wear down their opponents with superior physical play or pace? Do the players we are watching improve from year to year, or game to game, or even shift to shift at times? Does the team have a level of composure and seem to understand what needs to happen in order to undermine the opponent and create an opportunity to be successful? In evaluating the quality of a coach, it is not the cleverness of their plays or even the innovation of their system that matters. Creativity and innovation are important, but these types of coaches, because their loyalty lies with the system and not the players, can sometimes struggle in leadership positions. The three key components of good coaching - fitness, development and detail - are universal. They may or may not lead to a winning situation and talent deficits may lead to a losing record, but in that situation, we can see the seeds of success if a team upgrades their talent or natural development takes place over time.

The first measure of the quality of a coach, a commitment to fitness, is one that may not be visible to the average fan. Other coaches may more readily notice the fitness levels of players through subtle signs of fatigue or a persistent lack of execution late in games. The second measure is one that is more easily discerned by all observers. A good coach will be committed to helping their players improve. If you are in a situation in which you can recruit, then there is the possibility of improving by acquiring better talent. Even in this situation, the surest path to team improvement is player development. The ability to envision what elements of a player's game need work and then to help execute a plan that enables players to live up to that vision is a sure sign that you are watching an impressive coach. A commitment to player development requires that a coach has a firm grasp of their over-all system and the skills required to execute that system. It also requires that a coach not be so committed to the system that all they have time for is 5-on-5 practice to master the rote movements and outcomes. Instead the system is used as a tool to help players understand where they need to get to with their games. It gives them a framework for all the footwork and cuts necessary to get to the right spots and the skills needed to make plays from those areas. When working in practice situations, good coaches are consistently talking to their players and offering instruction about how they need to do things and what they need to work on. Execution is broken down to the level of the needs for each individual participant. There is also a willingness by both the coach and the player to work individually to maximize a player's development. As players improve personally, it also helps develop the team's depth and gives the coach more usable pieces to have at their disposal. Athletes, like most people, will have the best intentions in terms of working hard on their fitness and skills. They will profess their desire to do what is needed and lay out their plan in terms of how they will accomplish their goals. This is where a good coach is able to stay on top of their players and see that they adhere to their plan; to make them accountable. It is like the Confucius saying, "At first the way I dealt with people was to listen to their words and trust they would act on them. Now, I listen to their words and observe whether they act on them. It was within my power to change this." You cannot control the actions of others, but you can control whether you are aware of the actions of others. A lot of coaches will offer their players advice on what they can work on, but are not actively involved in seeing that their players are developing and following that plan. They see this as the player's responsibility. Quality coaching understands the importance of directing their player's skill development and playing an active role in helping them reach their potential. Good coaches also understand the motivating factor that personal development is to most athletes. One of the surest ways to keep players happy and working hard is to help them see the positive impact their improvement is having on them and the team. Players pay better attention, work harder and feel better about what is happening when they feel some sense of control. The only thing in a team setting that they have any real control over is their own improvement. This is a key reason to concentrate on this facet of coaching. It is easy to get swept up as a coach in tactics and game plans and how the whole should function. When you spend an inordinate amount of time on system development, players can lose their connection to what is happening, feel like the process is out of their control and grow frustrated and stagnant. When a player senses that a coach is invested in their development and cares about their growth, they are more likely to compete hard and pay attention to the things the coach is looking for. Player motivation is a key reason to be invested in player development. Once you have decided that player development is a key consideration to ensure quality coaching, it opens up a consideration that every coach who is invested in individual improvement must confront. This consideration is the conflict that exists between outcomes and development. Over the last number of years, there has been a slow evolution away from coaching for outcomes and more focus on coaching for process. In outcome coaching, the emphasis is on winning and desirable outcomes for the team. In process coaching, we believe that a certain style of play will be beneficial and, if we establish that style, then we feel that the outcomes are more likely to be favourable. In outcome coaching, we are seeking something that we do not fully control. Ultimately, we have no control over outcomes or other variables like the officials, whether we are home or away, weather, illness, etc. which have an impact on the outcome of a sporting event. On the other hand, we can control how we play. Attempting to get our players to execute and behave in a manner consistent with what we feel like we need to be successful, is something in which we should seek to have a direct hand. This puts the control back in the athlete's hands and even though we may not always get the outcome we desire, we can always measure whether we played the way we want. Most people in the coaching business now see process coaching as the right path to follow. Even in choosing to be a process coach, the end remains the same: we are still trying to produce the best possible outcomes. We can be happy if the outcomes are not wins, if we play well, but what if our decisions directly impact our chances of playing well? As we have stated earlier, the more veteran the team, the more likely it will execute well. Making the decision to play your more senior athletes will usually give you the best chance to play well and therefore, the best chance to win. This is why judging a coach on their team's win/loss record can be misguided. If a team is full of young talent, that talent, because it lacks the necessary experience to understand the plan the coach has laid out and the reps to build faith in that plan, they are more likely to unnecessarily deviate and chase other goals or means of execution, often in misguided notions that they understand what needs to be done. This is not necessarily a lack of discipline or respect, just youthful exuberance. Learning to stay on point is part of the growth of every athlete. Often coaches are teaching the right things, in the right manner. What is needed is the patience to see the process through. With these things in mind, and if we accept that athlete development is a necessary part of quality coaching, then we must accept that helping young athletes learn and grow is significant. What follows then is the question, are there certain outcomes that we are willing to sacrifice to aid the development of our players? Sacrificing these outcomes can come in many forms. It does not necessarily mean losing, although that is a possibility. It can mean winning by a smaller margin, or under tougher circumstances. In some instances, it can mean letting a game get away that you might otherwise have won. If you identify a player who has the right skills and makeup to be a finisher, a player who can make plays late in games, then there may be some negative results while you give them the ability to acquire reps in that role. Letting the bench log minutes in situations where leads have been built may squander some or all of that lead, but the reps acquired by those players are valuable and the long term benefits are harder to judge. Having games or tournaments where you are up front about the outcomes not meaning as much as the development opportunities for some or all players, especially in youth coaching is valuable. This notion is even becoming more acceptable at pro levels, where the need to play younger players is acknowledged to have an outcome cost, but "rebuilding" is an accepted part of the process now. If you consistently keep player development in mind in the planning of opportunities and outcomes, then you are better able to build a more consistent base for your teams and produce more even results over a longer period of time. Often teams are forced to suffer through bad seasons when they swing too heavily to relying on veteran players and then suddenly lose a large number of them for various reasons. The willingness to place outcomes behind player development at certain times during the season is a sign that a coach understands the long game and is invested in both now and the future. It also strengthens a team, makes all players feel better up and down the bench about their contributions, and makes a team tougher to defeat at the end of the year. When you are building your yearly plan, these are important considerations to think about. The need to be committed to player development in all its forms should be ever present.

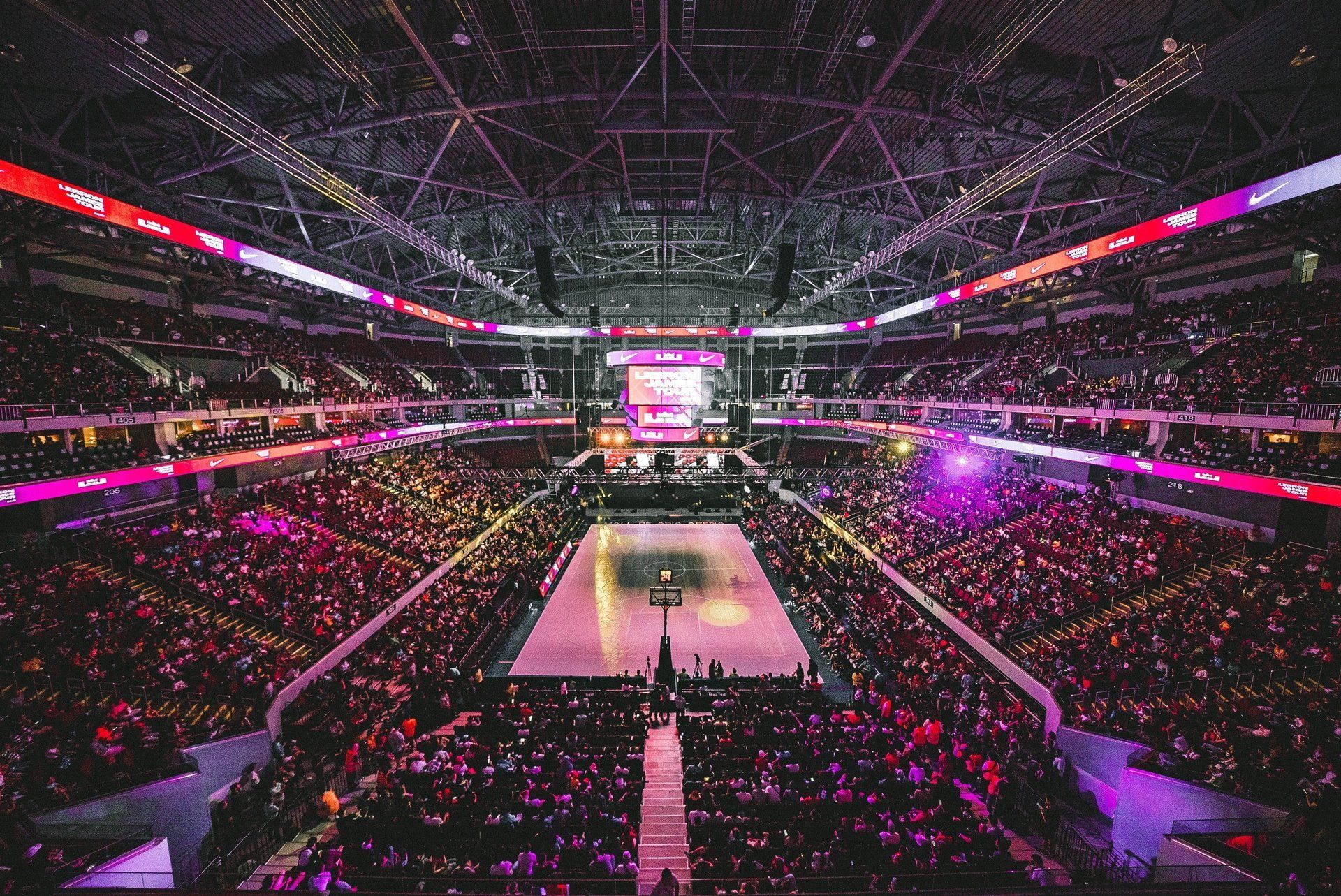

A long time ago I was lucky enough to be a part of a national NIKE development camp for basketball. At the camp, they had various speakers for the athletes and one was a physical trainer who talked to the athletes about fitness. In his talk, he reminded everyone of the old adage "mental is to physical as 9 is to 1." Then he flipped it around and said, in truth, "physical is to mental as 9 is to 1." At the time, I was a big believer in mental toughness and the mental side of sport and I found the flipping of the saying difficult to believe in, after all everyone prepared physically, how could it be the biggest difference maker? After spending more then a quarter century in coaching and athlete development, I believe that I now understand what he was saying. The first thing that all great coaches share is a dedication to physical fitness. Fitness is the foundation on which all great athletic endeavours are built. It is the base that carries all teams and athletes forward. It is an necessary starting point. The quickest way to turn around an unsuccessful sports team is to radically change the way athletes approach fitness and change the culture around working out. The fact is that the vast majority of athletes are not willing to pay the physical price to achieve any measure of greatness in sport. Sport is full of stories of coaches who enter situations and quickly let athletes go or cause athletes to get in better shape or work harder and then the team suddenly begins to enjoy success. The gauntlet is thrown down immediately. People will be in shape or they will not be welcome. The athletes that buy in right away begin to enjoy success and as the others see the success enjoyed by those athletes, it motivates them to join in the revolution. Soon the atmosphere has changed and working out is a must if an athlete wishes to fit in with their teammates. Fitness testing becomes part of the norm and the chance to measure one's work, drives some athletes to work even harder. The lower the level of sport, the more basic the training can be, but is essential to have a focus on training if a coach wishes to be successful. It may be easy to see why the focus on fitness is important, but how is it the most important? First and foremost, the emphasis on fitness instills a sense of discipline into what the athletes are doing. Work-outs become a focal point of the day and the way in which a player's body responds is measurable and easily felt. If one can be taught, led, or otherwise brought to develop a work ethic around physical training, it begins to grow into proper nutrition and many other areas as the athlete starts to feel better and craves to further that feeling. This all requires work and effort directed in the right way. All hallmarks of discipline. A coach can easily tell if their players are committed to training, if they are being productive. Athletes that complain about the work it requires to play are often tipping off the coach to the fact that they will resent hard work in practice and game situations and that they may lack the discipline or focus to be successful in the long run. The establishment of discipline that goes along with commitment to training is a great first step to success. Vince Lombardi famously said, "Fatigue makes cowards of us all." This is a crucial statement to the importance of training and physical development to coaching. Athletes rely on confidence to a great degree to be successful. The difference between two very talented players in a competition is never who wants it more, but rather who believes more that they will get it. What is the foundation of this confidence? I have always believed that confidence flows from preparation. An athlete who feels totally prepared will be, by extension, more positive about their ability to achieve. Competing requires a tremendous effort, in a way that being noncompetitive does not. If the athlete feels they have paid the right price to be where they are, then they are more likely to respond positively when they are in a difficult situation. They are not going to shrink from the moment. This may be the true importance of physical training. Although some athletes may have deep rooted feelings of inadequacy that may cause them to fail at key moments, most of these feelings can be overcome through proper preparation. Most athletes succeed because in the end they feel they have gone through too much to fail. Tough physical work-outs help to build that sense in athletes at every level. The fitter the team, the less likely it is to "choke." Finally, in order to show the true importance of physical conditioning over mental work, one has only to ask what happens when the physical breaks down? Athletes can have the most elaborate mental routines and exercises to keep them on track, but if they fatigue, the only thought passing through their mind will be, "I am exhausted!" It is easier to suppress fatigue as a factor if you have continually, and in many different ways, worked your body past your preconceived notions of your limits. Every person has notions about what they can and cannot endure. The breaking of these limits is essential to any athlete reaching success. The human body is a wonderful machine that can endure and adapt. If it is stressed in one way, it will work to compensate and that will allow it to be stressed further the next time. Muscle development, flexibility training, aerobic work, all forms of physical fitness are all about stress and growth. As each potential barrier is met and shattered, athletes get the sense that if they are willing they can accomplish anything and that fatigue is a mental state that can be overcome. In some sense this is an exercise of mind over body, but the mind needs the physical work in order to form this conclusion. Still need a little more convincing? We have all watched The Last Dance, with the great Bulls teams and Michael Jordan. Think back to the Bulls and when everything changed and they decided they would beat the Pistons and be champions. It all started with the athletes as a group, becoming dedicated to the weight room and working out at a level they had never experienced before. It gave them the strength, endurance and confidence to leave all their former doubts behind and become champions. It all started with a dedication to physical training. In the end, the lack of physical preparation for an athlete is decisive in outcomes. If you want to be a good coach, or player, the starting point is always physical prep and helping to motivate your athletes to pursue their best state of physical readiness. This is the foundation from which all other achievement is possible. Mental and spiritual development can only follow when the body is in order. For these reasons, all good coaching starts with a focus on physical fitness.

The quality of a coach has long been a point of contention. What exactly marks someone as a good/great coach? In most circles, the win loss record is the main measure. This is an interesting argument. The teams of a coach that have won on a high level, are champions, they have drank from the cup, therefore the coach knows what they are doing, they are good at their job. We have this fed to us again and again, by the media, the people we know, the public, everyone clamors for winning, that is the ultimate measure. After all, "the proof is in the pudding", and in this case it is a very public bake-off, so we can see immediately whether the coach knows what they are doing. Measuring the quality of a coach is easy then: it is as simple as whether or not they are able to win. The problem with this analysis is that it is too simplistic. With the advent of advanced analytics, perhaps no statistic has taken a bigger beating then the win. In baseball, winning is seen as everything from contingent on too many factors, to just the result of luck; being in the right place at the right time. This debate has raged for over a decade, whether the win has any value in measuring the quality of a pitcher. We are at the tail end of that debate and to argue it any further seems futile. The win has lost as a measure of success. Too many outside influences and factors have to be considered. If we are so ready to accept this as fact when measuring a player, then given their connectedness, which we have already argued, we have to also accept that it has no value in measuring a coach. The coach relies on the talent of their players, the quality of their support staff, the resources available to them and sometimes, just plain old luck in order to help guide their team to victory. There are just a lot of factors outside the control of most coaches to reliably use winning as the sole measure of success. In fact, you can probably be even more definitive in stating that no coach, anywhere, at any time has ever "won" a game. Plays are made by players, execution is on the people who are in the fight, no coach has ever sunk the winning free throw, kicked the game winning field goal, or fired home the penalty shot that wins the shoot-out. It bears repeating at this juncture, "the better the talent, the better the coach." If winning is not the measure of a coaches value, then we are left to look at other factors. Most people, if they admit that coaches are not to be judged by random victories, will often turn to style of play questions. How well does a team defend? How complex is its offensive execution or system? Is it a pleasing team to watch play? Quality coaching then is simply a measure of the quality of a team's play, after all, that is what the coach has installed. Their job is, take the talent on hand and build a system of play that will give the team a chance to be successful. In this sense, every time the team takes the field of play, we have a referendum on whether a coach knows what they are doing. Once we have watched enough games, we can, with confidence, pronounce the quality of the coach based on the team's execution, system and performance. This seems logical and the best measure of a coach. The quality of a team's system can be measured whether the team has talent or not; winning or losing are not part of whether a team plays solid systemically. While this seems like the perfect measure, it fails on at least two important considerations. First, and most importantly, there is a reason that teams that win championships in most leagues are stocked with veteran players. Veteran's have had time to figure out what matters to them. They have explored their own games, gone outside the system and made their names. They have had a taste of recognition or fame and have begun to glimpse their own mortality. Unlike young players, they know this is not forever; that father time is undefeated. They are prepared to be coached, listen and execute. In short, they understand the importance of being productive and knowing the script. With this in mind, we can see that often, execution has less to do with the quality of the coach and more to do with the type of players available. A slightly inferior coach working with veteran talent, that have a high desire to succeed and good sport IQ's, are likely to play a very good game, regardless of the inferior instruction. Similarly, a very good coach working with inexperienced talent that is still trying to establish its place in the league is likely to struggle at times with execution and quality of play. What is needed is not a better coach or firmer hand, but more experience for the players. The best example of this is probably the career of Doc Rivers. Rivers was hired by the Boston Celtics as they embarked on a rebuild. Over several seasons, his team struggled to improve and were borderline unwatchable. Things were so bad, and the execution on such a low level, that several prominent sports journalists campaigned for him to be fired. Instead the Celtics stuck with him and then, in one off-season, landed Ray Allen and Kevin Garnett and made some smaller moves to move out younger players for veterans and marched to a championship season. Rivers is now hailed as one of the best NBA coaches of all-time. His coaching ability did not change, but the talent and preparedness of the people around him did. The second consideration in this analysis is that often beauty is in the eye of the beholder. What one analyst considers to be cornerstones of solid play are not necessarily what every analyst believes are the key ingredients. This is a subjective measure, perhaps too subjective to be of any real value. Do you prefer a fast tempo or a slow one? A pressure defense or a conservative one? One person's trash is another's treasure, so to speak. A coach may be condemned for playing a particular style of game, or a style that ill fits their talent, but there may be a grander scheme in place. The idea may be to establish certain habits, or a certain style of play, with an eye to overhauling the available talent to better fit the system. While this may produce some ugly short term results that seem to indicate the coach is not prepared, as the roster takes full shape and the right moves are made the approach may start to make sense. People often act like the coach has had some major breakthrough, or epiphany, that has led to better results when, again, it was simply patience that built the approach. Thus, style of play can be as unreliable a measure as winning when it comes to glimpsing whether someone is a quality coach. It is certainly true that one should glimpse the elements of solid play in the team of a good coach. There should be a plan and one should be able to discern what that plan is, at least from time to time. The fact is, that like winning, there are too many variables in execution for it alone to be the judge of whether a coach is good at their job. If we leave winning and style of play considerations behind as unreliable measures of whether a coach knows what they are doing, then how do we proceed? What elements do we look at to help us make sound judgments on the quality of the coach we are examining? Having given this much thought over the years of my involvement in sport, I have come to the conclusion that there are three common components to which you can boil down good coaching. As I have stated, my predisposition is as a minimalist, and therefore I am looking for things which are common across the board. You can create a more exhaustive list of elements, but then you will find some of these factors in various good coaches but not in others, We want those aspects that you will find in any solid coach. In that regard, c oaches are responsible for establishing the culture and habits of a team. Through their teaching and modeling, they demonstrate what they expect and what they will accept. If we take a broader interpretation of success, looking not just at success on the floor, but success of their players off the floor, achievement on many levels, personal and team accountability and all the positive habits that we have come to value over time, then we can more accurately judge someone's worthiness. If a coach is successful it is likely because there are certain habits, or commitments, that they make, which will allow them to create an atmosphere where their teams can be "successful" on many levels. It is in looking for common traits among successful coaches that we can begin to see the common factors which make for a great coach. In the next three blogs we will explore these three factors one at a time.

After a one month detour we return to our examination of coaching, we have journeyed together to arrive at a satisfactory definition of the job of a coach and the job of a player and how they relate to one another. The next step is to explore how these parties can evaluate the job being done by one another. If we accept the concept that players and coaches are, or should be, working symbiotically for the betterment of each other, then it follows that each must have the right, or even the responsibility, to critique and aid the other to do their best work. In many circumstances, coaches can be anywhere from reluctant to hostile to the idea that players can offer meaningful insight into how they should perform their jobs. They are younger, less experienced, in most cases have less knowledge of the sport. How can they be trusted to offer anything meaningful in terms of how the coach performs, or what needs to be done? While these are valid concerns, players do have the right to express how they feel about a situation and whether the situation is meeting their needs. These expressions can often lead to an understanding between the coach and player(s) that is deeper and more fulfilling. In order to reach this detente, it is usually important to acknowledge some common pitfalls and create valuable common ground. By far the biggest pitfall is the "alter" of playing time. In any organized team sport, players often will make their first judgement about coaching based on whether, or how much, they play. "Did the coach give you opportunity?" This may be the question, but the answer all too often depends on whether the athlete actually got to play any great amount of time. Therefore, in order to reach any true understanding between player and coach, it is essential that the player understand how decisions of whether players are doing their job are reached . We lay down the job of a player as being able to produce. You must have a solid answer as to what makes a player productive. Anthony Hopkins, the great actor, when asked about the epitome of acting said, "Know your lines." Katherine Hepburn, another truly outstanding actor said even more bluntly, "...just speak your damn lines!" The baseline of productivity for an athlete is very similar for me, you cannot hope to be productive if you do not know what we are doing. Some systems must be toned down to help certain gifted or instinctual players contribute, but there is a certain baseline where an athlete must be able to understand the goals and objectives of the system as it is constructed. They must know where to be and what is asked of them in various situations. The basis of productivity then is to know the script. The first judgement a coach should make is whether a player is prepared. Can they step on the playing surface and execute? When they deviate from the plan, or script, can they explain why it was necessary given the opponents reaction? Do your athletes understand that an unprepared player will not be productive and therefore their opportunities will be limited? Once an athlete meets the baseline of being prepared, then they have earned an opportunity to try and contribute in a game setting. At this point, there must be an understanding between the players and the coaching staff of what the weights and measures are that will be used to assess whether a player has been productive. In my many readings about coaching, I came across an idea from Anson Dorrance, the highly successful women's soccer coach at the University of North Carolina. He uses what he refers to as a player matrix. The matrix involves taking several statistical and fitness measures that he values and using them to rank his players from the best to the weakest. He finds that when the matrix is complete it gives him a true reflection of where his athletes fit in his program. I have adopted this concept to my coaching as well, using analytical measures of my players to fit them into a hierarchy of production. Using this hierarchy, we can get a true sense, from a statistical point of view, which players are being productive given opportunity. There can be some deviations due to small sample size, when players are used and whether they play against similar levels of competition. What I have found is that if a player performs well against lesser competition, they have earned a chance against better comp. If their production falls, then we have an answer as to whether they are prepared to play. As coaches we often rely on the eye test to settle whether a player should be given a chance or whether they have performed well. Often, slotting players into the matrix will reveal an underutilized player, or a player who is more productive then the eye test thought. The team's performance can often benefit from these revelations. Similarly, the matrix may reveal a player who is over-utilized, and does not produce value for the team in the role they are being asked to perform. The two biggest issues in coaching that the matrix helps to overcome are, the role of first impressions and falling in love with hustlers. In the first instance, a coach makes an initial judgement about a player and can often be blind to that player's improvement and work to be better. A matrix can help reveal a player's productivity that we have been blind to because of our first impression. In the second instance, coaches tend to develop a real bond with the player who works extremely hard, gives it their all, so to speak. This player can often be a poor offensive finisher, find themselves out of position a fair amount and place undue stress on their teammates to account for their shortcomings. The matrix often reveals their lack of production and can cause us to properly evaluate where that player fits in our rotation. A poor placing on the matrix is not the kiss of death to a player, people improve performance all the time, but it can help them understand their current position on the team, why they play inconsistently and where their production needs to improve. A player who has a good matrix result but does not play consistently because they fail the first test, knowing what we are doing all the time, is a player who will be a very solid performer once they "know their lines." Bringing the matrix out in front of your players a few times a year and allowing them to see where everyone ranks is a valuable exercise that often helps people be realistic about their performance and how they are playing. It also makes it more difficult for a player who is complaining to their teammates about their situation to find sympathy if they are not producing. This helps hold the coaching staff accountable for their decisions as well, it creates transparency in what is being done and helps build trust between the coaches and players. A productive player has the right to question their role, what is asked of them and whether it is sufficient. Every player is different, and as a close friend of mine is fond of saying, "God makes first cuts." In other words, it is important for athletes to keep in m in d when evaluating their circumstances, what are my physical gifts and limitations? It is possible that they can be successful and productive within a limited role, but that productivity does not hold up in a larger sample size. It is also possible that a player can be very productive in a practice and training arena, but not ready to produce in a competitive environment. The key to these situations being understood is the communication that exists between the player and the coaching staff and the understanding they have about how these situations are being evaluated. Despite all of this, it is possible that a player will simply choose not to believe that they are unproductive, to doubt the system or fail to understand their limitations. It is not always negative for a coach and player to part ways. We will discuss the issue of trust in depth at a later time, but when an athlete does not trust or fit the system they find themselves in, there is nothing negative about moving to a new situation. It is positive to explore all possibilities to make a situation work, but there are occasions when the system in question is not the right one for that athlete and allowing them to move on to a set of beliefs that better reflects what they appreciate is positive. A player should make sure that desire does not cloud their judgement. "Am I unhappy simply because I desire more?" Versus being unhappy because I believe areas where I can be productive are limited by the system employed by this particular staff. Knowing when it is best to retain an athlete and when it is best they move on is certainly an important part of effective coaching. There are times when to properly give an athlete their best opportunity you must let them, or even direct them, to look elsewhere. Our first job was to decide what it is a coach, and by extension their players, have as their primary jobs. The need for a universal, simple answer that is both applicable and can be evaluated was necessary. This is an essential starting point for the journey that follows and any person who wishes to get the most out of their coaching career needs to contemplate these questions and arrive at their answers. For me, the role of the coach is to provide opportunity, while the role of the player is to produce. Once we have these judgments in place and we have an understanding between the two bodies about their respective roles and how they will be evaluated, then we are ready to move forward with our examination of coaching.

We are going to take a little detour from our dive into the nature of coaching to examine the goals and objectives of youth sport. There has been a lot of discussion lately around how the NLBA organizes and executes its youth tournaments and programs and what those programs and tournaments should look like. I believe it is important for parents, athletes and coaches to have a solid sense of what we should be aiming for in youth sport and what a healthy youth sport program looks like. The main aim of any youth program is to build a solid base of participation for its sport. In other words, to reach the largest number of athletes and energize them about participating. I think we can all agree on that point. The number one motivation among young athletes is fun. Most young people want two things from their participation. One is to be active and run around, and second, they want to learn; to be shown new things and how to do them. That is a great platform to begin with. Those responsible for programs need to ensure that any youth program gets children active and moving with a minimum of lecturing or talking by the coaches/instructors and also teaches new skills. We need to make the atmosphere as non-threatening as possible. This means we should not be singling out individuals at early ages, but instead work with the team dynamic as much as possible. Giving individual feedback on how an athlete performs a skill is fine, but comparisons such as, "Everyone should do this like Johnny.", or, "Why can't you be more like Sarah?", can leave young children confused and stressed. Giving out individual awards can be just as confusing for young athletes as it can cause players to be stressed or not understand why they did not get an award or even cause an inappropriate sense of accomplishment for an athlete and/or their parents. The reality of youth sport is that we have no idea based on young players who the best performers will ultimately be. The early maturers, the first players to learn how to make a right handed lay-up, the first person with a functional jump shot, any of these can all look like super-stars in youth sport, and with individual recognition comes a sense that I may not need to keep working or getting better - I am already the best. As these athletes age, they may no longer be the physically dominant performer they once were. I was the tallest child in my elementary school and then never grew after grade 5. As athletes go through puberty, they can slow down, not be able to keep up with the physical demands, or their peers may become more coordinated, grow more and be more athletic all leading to them surpassing the early "stars". The result can be extremely frustrating for the parents and athletes as they try to understand the changing environment. We may also have chased off ideal candidates for our sport because they do not receive any early recognition and they feel the sport is not for them. I remember my daughter taking part in a youth sport program when she was 5 that she really enjoyed. It was her second year being involved and she never had to be encouraged to go. At the year end session, the coaches gave out evaluations and on one evaluation a coach had written to another youth that they had a great future in the sport. At 5 years old, this had nothing to do with skill execution; it had to do with body type. The truth is you have no idea what the body types of any of those athletes will wind up being. When my daughter then heard the coach say this to the other athlete, she asked why she said that to the other child and not her. She did not return to that sport program simply because she did not believe that they were interested in her. Individual recognition at early ages can be damaging in a lot of ways and that is why the NLBA avoids it. When I first came to Newfoundland, I ran into something called "fair play". It was the first time I had ever seen this notion and to be honest, as an elite coach, I did not really support it. I thought it would be better to have athletes playing "real basketball." Later in life, when my son entered junior high, I decided that it would be good for me to coach his team. My three years spent in that environment convinced me that fair play was the best system to encourage player development at the younger ages and really up through junior high. It forces the coach to work with all their athletes and not just those they see as "gifted". In order to compete, you need 10 functional athletes, so you cannot ignore the other players to focus on just the 2 or 3 best players. We know that many of the physical ailments that afflict athletes are overuse injuries. We also know that the risk of injury climbs exponentially with the build up of vast amounts of playing time. I often see parents absolutely indignant that coaches do not play their children during games. I have often said that parents should be just as indignant if a coach plays their child for an entire game with out a sub. That is just as damaging, and potentially more dangerous, than not playing a child at all. Saving coaches from themselves with systems like fair play is vital to a healthy basketball environment. A coach should aim to play as many players as possible. You may not be able to find every player a meaningful role in every game, but you can certainly find every player a meaningful role in every season, to help keep them engaged and attached to the sport. Coaches often approach youth sport with the wrong goals in mind. How often have I heard coaches say, " Life is about winners and losers.", "We have to prepare these young people for the real world.", "It's all about competition!" You will never meet a more competitive person than me. I compete for everything, I was legitimately upset in school if someone passed in a test or exam before me. If I am doing it, then I am trying to do it well and trying to beat those around me. As with most people, I often project my hyper competitiveness unto other people, but my life has been full of constant reminders that not everyone feels the same. In fact, young athletes rarely pay attention to the score or outcome. I can remember coaching my first club U14 game. We were playing a strong team and the game did not go well. We lost by between 20 and 30 points, and as the game was winding down, one of the players turned to me and said, "Are we winning or losing?" It was a genuine question, she had no idea of the outcome. Young athletes just want to play, they want to be on the floor and run around, the outcome or its significance is often the furthest thing from their mind. It is important, especially at young ages, not to project your hurt or disappointment about outcomes on your athletes. Not to make them feel an out sized sense of loss, or embarrassment about a final score, that they would not otherwise worry about. As long as players are getting a chance to play and run around and experience and experiment with the game, they can have just as much fun losing by 30 as they can winning by 30. But if their coach, or parent, is upset and embarrassed, they will feel that shame, because they care about their coach and parents and gaining their approval. It will diminish their enjoyment and may even lead to them stepping away from the sport. You must be able to separate people from outcomes. Just because a group of people lose a game, it does not mean they have a flaw in them as humans or a shortcoming in their character that causes them to lose. Your reactions to them should be the same after a win as after a loss. If you are not capable of that, you may not be cut out for youth sport and there is no sin in that. You may be best at coaching older athletes who have a grasp of outcomes and are seeking to be successful. You still need to separate the player from their performance and care for people whether they play well or poorly. Older age groups may be emotionally more prepared to deal with the in game consequences of not playing well. The other part of this is the necessity to allow youth players to experiment with the game, even if it has negative consequences in terms of the outcome. We had a taller player on one of our club teams who loved to grab rebounds and just take off dribbling up the floor, only ever using her strong hand, and always with her head down. The inevitable outcome of these wild forays with the ball was almost always a turn-over. My assistant finally turned to me and said, "We have to stop her from dribbling." I replied that we could endure these mistakes and that if we did we would be rewarded. After one year, the player had become very good at pushing the ball forward, dribbled with both hands, was hard to stop driving to the basket. She was one of the better players in her age group. My assistant admitted that I had been right not to curtail her dribbling. The long term outcome of allowing that player to explore her game was a more confident, skilled player, who now can do a lot more things in a game. It is important in youth sport to keep in mind: allow players to grow, do not project your emotions unto them and do not make the experience all about competition when it should be all about growth, development and fun. The NLBA reflects on those following things as the most important aspects of youth sport: fun, activity and learning. Those should be the guiding aspects of any youth program and any parent judging a youth program has the right to expect those three elements to be involved and question if anything interferes with achieving them. If you are coaching at that level, You need a passion for development. You have to genuinely enjoy seeing athletes improve above anything else. There should not be an over importance placed on any single player, whether that comes in the form of how shots or possessions are distributed, or whether it comes in personal recognition above team accomplishments. Our youth tournaments are designed to promote activity and passion and avoid the negative aspects of early recognition like an out sized sense of importance, pressure or anxiety associated with performance, or a lack of retention because of a lack of recognition. We allow larger team sizes and more flexibility with line-ups. Any coach who asks players not to participate in order to allow fewer shifts is not in line with what is best for all athletes and sport in general. Parents should have concerns if player rotation is used below grade 7 or 8 when it is mandatory to play certain numbers and not necessarily all players can play every game. We need to have an environment where every child has a sense that they could possibly be a good player. If over time, they come to their own conclusion that they lack the passion or physical ability to play the sport at higher levels that is fine, it is their decision, but we should not make choices at the youth level that preclude athletes from arriving at those decisions on their own, or by de-selecting them at early ages. The NLBA's choices and how we structure our programs are leading to growth across the province, more teams, more players and more tournaments. The game is returning to healthier footing outside the city with many youth sport champions. If we all continue to emphasize the right elements of youth sport, the game will continue to grow in a positive manner.

The first consideration is always what is the role of the coach? Before we can consider what makes someone a good coach or how they should do the job, the first decision is what do we think they are trying to accomplish? No judgments are really possible until we fully understand what the coach is supposed to be doing. In making this judgment, I also find it necessary to link the two parties involved. The coach and the player are really two parts of the same continuum. Often people try to paint them as antagonist s; two adversaries battling each other for control. In my world, the coach and player(s) form a relationship that evolves over time and understanding that relationship is crucial to building success. Thus, understanding the role of the coach equally requires understanding the role of the player. Before we decide on the role of each, it would probably be valuable to examine this relationship. Like most relationships found in nature, the coach-player dynamic often follows one of two paths. They are either parasitic or symbiotic. In a parasitic relationship, one feeds off the other. If the coach is parasitic, they see athletes as a means to an end. They are simply vehicles that can drive winning. They are to be used while they have value and discarded when they no longer provide a return. In this type of coach-player relationship, there is little room for concern with development. Players are given the expectations and given a chance to live up to them. Failure is often seen as a personal short coming and not a need for improvement. The player is not successful because they lack some personal or moral fiber that is necessary to succeed. Coaches devote most of their time to the players who perform well and often ignore those who do not. When repetitions are handed out in practice, the good players get the lion's share while those who are struggling may not get any. There is a lot of turn-over in personnel and little attention is paid to the atmosphere around the team. The players who are happy are those who are rewarded and little thought is given to those who are not. This kind of atmosphere can still produce a lot of traditional measures of success in the form of wins, and even championships, and thus can continue for a long time. It is not uncommon in these circumstances for players who move on from parasitic type relationships with their coaches to struggle with what comes next in life. They see little value attached to their work and begin to believe that control resides with the person in authority and not themselves. They are used to being used and have seen no value in questioning that reality and so the tools that are necessary to function in the world, perseverance, diligence, work ethic can atrophy and rot. The ultimate judgement of this type of relationship is not in the moment, but in the long term. It is not only the coach that can be parasitic, it is also possible for the player(s) to adopt this stance as well. When the relationship is parasitic in this direction, the player often sees the coach in the Western myth archetype. From this view, the team will be successful because of the prowess of the coach and it falls strictly on the coach to produce this success. The player is exonerated from any culpability in outcomes. Often player leadership is weak in these situations and the players siphon their energy from the coach. The coach is expected to teach, lead, make all decisions and bear all burdens. This model is usually far less sustainable than when the coach is parasitic, mainly because of the stress placed on the coach. The burden is great and often the coach feels exhausted or burnt out. For these reasons, coaches placed in this situation will either move on or make changes. The simplest change is just to revolve the personnel. The more difficult and meaningful change is to confront the parasitic nature of the relationship and, in confronting it, see if the athletes can be educated to conduct themselves in a better manner. The athletes need to see the value and the limitations of coaching, no matter how good, and accept the necessity of contributing their 50 percent toward the success of the team. Often times, when teams are young, the players will lean too heavily on their coach and create this kind of parasitic relationship. This is not a flaw in the players, merely a lack of the necessary experience to be able to take control themselves. This means that having parasitic players is almost a constant truth, unless your team is consistently stocked with veterans. The process then is one of helping players to move through this early stage and on to a more positive one. The most positive type of relationship in coaching, like in nature, is a symbiotic one. A relationship in which both the coach and the player benefit. They work together to produce an atmosphere where success is possible and development of all involved is valued. In a symbiotic relationship, the coach is concerned with the development of all their players. Here, repetitions are available to all, time is spent with all players and everyone has a voice, regardless of how much or how little that athlete may contribute on the floor. Concern is given, not just to how the athlete functions in a playing atmosphere, but how they function off the playing surface as well. Athletes who are part of this type of system are well prepared for life away from sport and often have little trouble carrying over their success. They have made the necessary connections to why things are done and what that means for whatever comes next. They have leadership skills and are comfortable in high pressure situations, as no attempt has been made to shield them from these realities. Because they have walked beside the coach and not in their shadow, they are ready to move beyond, which in many ways is the ultimate compliment to any coac h. Players, who function in symbiotic situations, are those who have a strong sense of their own value. They understand that they have contributions to make and actively seek to engage the coaching staff in discussions based around strategy and the "whys" of what the team will attempt to do. They take leadership roles in dealing with fellow athletes and are not afraid to speak up when players are not behaving positively, or providing their 50 percent to the equation. They do not leave all the monitoring of the locker room to the coaches. They are willing to make sure the culture surrounding the team is positive and headed in the right direction. They accept that the produc tion of a successful team, in the true sense of the word, is the responsibility of all those involved. As strong role models to their younger teammates, they help ensure that a commitment to a symbiotic environment remains in place even after their playing days conclude. In the best symbiotic environments, the players will eventually evolve to a place where they often seem not to even need the coach. They know how to prepare themselves, pay attention to detail and perform at a consistently high level. This allows the coach to turn their attention to planning and development, being secure in the knowledge that their team will always be prepared to perform. The ultimate goal is to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Because your leaders are well versed and understand your expectations, they carry them into everything that your team does whether you are present or not. Your players begin to hear a voice in their head when confronted with a choice and that voice slowly becomes yours, allowing you to have an influence even when you are not present. Rather than forcibly trying to control things, you are allowing your sense of caring and proven track record of decisions to build influence throughout the team as the players grow their own personal leadership skills. When you release your players from attempts to micromanage them and show the faith you have in them to make decisions and move forward, the gains in confidence and improved performance can be astounding. As well, the bonds between the coaches and the players are much more enduring and can often last a lifetime. Giving thought to the type of relationship you wish to have between the coaches and players on your teams is often a first step to building a successful coaching career.

Much is made of coaches needing to have a philosophy to guide them, but little is out there that really helps a coach consider what actually goes into a philosophy. Usually, the surface is barely scratched and style of play questions are offered up as philosophy. Do you play fast or slow? Physically or with finesse? What parts of the game do you emphasize? All of these things are important to consider, but are they really a philosophy? You most certainly do need a style of play, but you just as importantly need to understand the beliefs that underpin what you are trying to accomplish. Why are you in this business? What do you have to do to be successful? What is success? These fundamental questions are what truly defines a person's philosophy. Many coaches choose to believe that the sole role of a coach is to win games. They settle into a comfortable rut of running the same systems year after year and, if the talent is right, they pile up a great number of victories. In the end, the connection to their athletes is transitory and their impact potentially forgotten if they imparted nothing to their athletes but that system and a few victories. Taking time to consider the deeper elements of coaching, I believe, allows a coach to have a stronger and more lasting connection to their athletes. The other important consideration, for the formation of one's philosophy, is your own underlying belief system. For me, the central theme is that all true knowledge is ancient knowledge. When you read and study extensively in ancient works, and particularly eastern philosophy and religion, you can gain an understanding of things that can be very beneficial in a sporting venue. The western world paints a certain picture for people about what is valuable and that picture is reinforced in almost every image or thought we are presented with. If you coach in a team atmosphere, this can prove very challenging. Take the notion of freedom. In the western world we are taught that freedom is the right to self-expression. That individuals need to be able to express themselves, whether verbally, through body art, or whatever means necessary. Relinquishing that right is seen as damaging or negative. Eastern, or ancient knowledge, paints a very different picture. True freedom is instead the ability to release one's individual needs and submerge oneself in a group. If I am willing to forgo my own desires and wants and instead place the good of the group in front of myself, then I can truly be free. The release from desire, especially for things we do not control, gives us the ability to express ourselves totally and be our best selves. After early ages, when fun is king, there are many athletes who stay involved in sport because they crave recognition, playing time, status or championships. The simple fact is that most athletes do not control these elements. It behooves an athlete to release these desires and embrace the fact that the above elements are not yours to decide. You just play, not for what you receive, but because it is "you" to play. Being one with your sport, where the pure love and enjoyment that comes from participating is your main motivation, is a difficult state to attain, but once there, it is the most enjoyable and fulfilling. Bruce Lee spoke often about the "non-graspiness of being." Not always seeking to be something or attain something, but instead living in the "now." Living in the now is the ability to see every event not in a "law of averages" type of conglomeration, but as a separate event. Trying to control events can lead to anxiety and poor performance, while just trusting your preparation and flowing through events allows for an unblocked performance. Anxiety is a result of grasping for things we do not control or attempting to live outside our limitations. If you do not know, or accept, your role, then you will seek to change it, or try to control situations you do not have control over. One can seek to improve themselves and their situation while simultaneously accepting their limitations and working to create their best self within them. If you are not grasping for what is out of your reach, it is easier to more honestly judge your performance. Many athletes in the current world base their own assessments on what they wish to accomplish and not on what they actually do. In the words of Yoda, "there is no try, only do or do not." Your assessment as an athlete is not whether you are trying, but whether you are accomplishing. If you are not graspy, then you can see more clearly what you are actually doing and what you must accomplish to be successful in whatever role the group needs you to fulfill. Finally, you can also see how fulfilling that role can bring you joy. If this is the basis of my philosophy, then we can see how the first step for me down the road to coaching is getting my athletes to buy into the need to submit themselves to the team. For them to get enjoyment through the success of the whole first and that their own role, however big or small, brings satisfaction for being done well. It is important to have this over-riding ethos in place so that every other decision that is made can flow from it. Once you have a "vision", so to speak, for your coaching career, you then need a "mission": What are we emphasizing on a day to day basis with our athletes? What are our non-negotiables? What does every athlete need to be willing to do to succeed or find a home in my program? It is always fascinating to see how many coaches have not considered these points before. In attending a coaching clinic this past summer, I heard Jay Triano, a national team coach, a two time NBA head coach, talk about how at the age of 61 years, he was just documenting his core values as a coach. It is vital to any coach who is trying to format their philosophy to understand these core values or non-negotiables and even more importantly document them. I have always believed in the power of three; three key ideas, three statements, three rules. Three is a good number. It is about what people can remember off the top of their head. For this reason, I try to limit these types of processes to three key elements. For me, my three core values are: 1. Timeliness - this is the most important. All you are given in this world is time, and you want to make sure that you do not waste it. Players and coaches need to be early to events, practices, meetings and games. A person who is late holds all the others as hostages. Will the coach be upset? Will there be a problem? It causes a lot of stress. Being timely eliminates all that drama. Furthermore, we only have a certain amount of time together to work on things. Do not waste that time with poor effort, bad execution, or a lack of caring. Make use of the time we have to learn and improve. 2. Discipline - be in control, make good decisions, discipline yourself in all things. Not just in your play, but how you carry yourself, your work/study, nutrition. All elements should bring with it the desire to be better. Make sure that you are mindful of others and control yourself in all situations. This has been one of the great struggles of my life and I have tried to learn from it and ensure that others do not head down a path that is not productive. 3. Passion - be all in, bring love and joy to what you do and best energy to your pursuits. Do not merely show up and go through the motions. Be enthusiastic about what you are doing and the opportunities that are in front of you. For me, my over-all philosophy starts with the need for people to be in the now, and release their desires for personal gain. We are a team and you need to submit yourself to the team. The combination of being in the now and releasing your desires will help you find a happier more enjoyable sporting experience. Once you are willing to buy into the immediacy of what we are doing, then we are governed by three principles: timeliness, discipline and passion and those that can bring these traits will be more successful in our program. From here, your next step on this journey is to take the time away from other concerns to make sure that you write out, and you have a strong understanding of your over-all philosophy, as far as basketball and life goes. What are your core principles? What do you expect of your athletes? This exercise will be invaluable and will allow you and your athletes to be on the same page, creating a more harmonious team and a better platform from which to have success.